| February 15 2025 |

Coast-to-Coast Winter Storm: (2/13 - 2/17)

By: Peter Mullinax, WPC Meteorologist

Meteorological Overview:

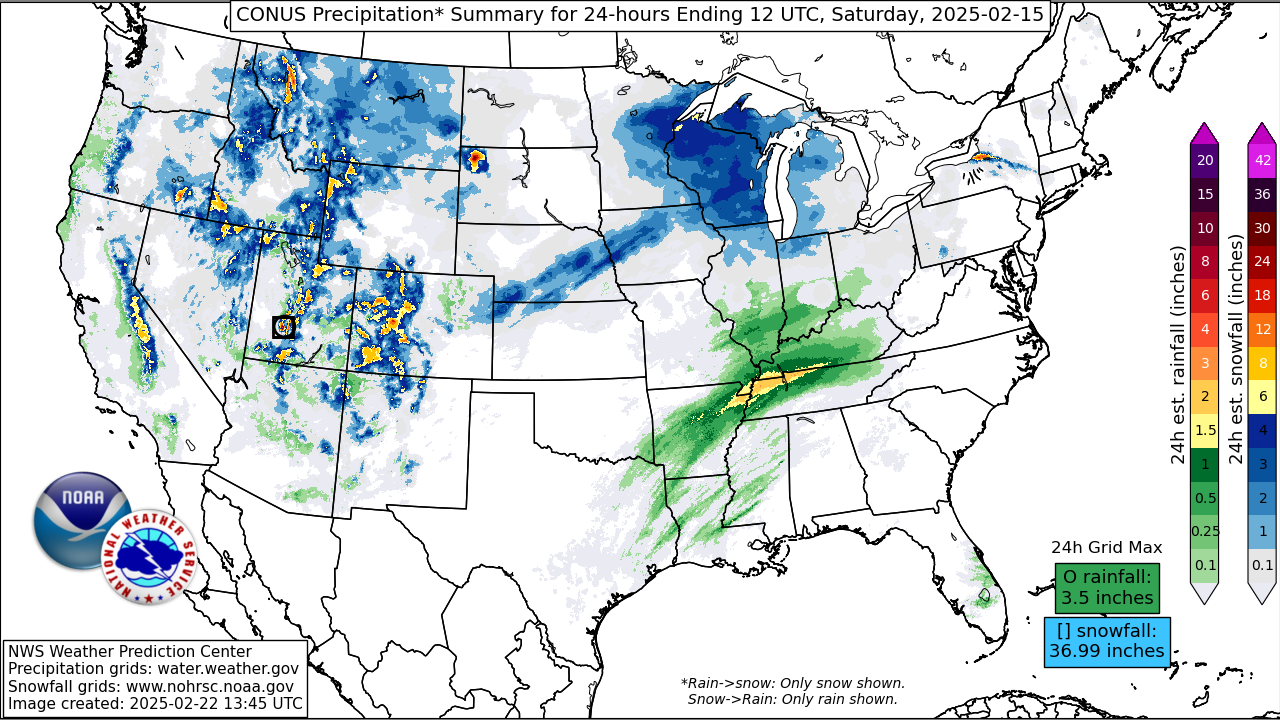

The origins of this powerful and destructive winter storm began in the West as a Pacific storm system directed a strong Atmospheric River at California the night of February 12 and into the day on February 13. NAEFS situational awareness guidance showed IVT values topping 750 kg/m/s at 12Z February 13, which reached the 99.5 climatological percentile for that time of year in the CFSR climatology. This storm was associated with a potent upper low that was responsible not only for the atmospheric river but colder temperatures aloft that supported heavy mountain snow. Not only did this storm and its accompanying atmospheric river produce heavy snow, but it also led to a dangerous food threat due to excessive rainfall from the Northern California coast on south into Southern California. The aforementioned anomalous IVT would extend into the Southwest U.S. with >300 kg/m/s values as far east as the Wasatch Mountains of Utah by 00Z February 14. The stream of rich Pacific moisture advanced well inland; from as far north as the Cascades and Northern Rockies on south to the Southern Rockies of northern Arizona and New Mexico. By the morning of February 14, periods of snow would persist across the Intermountain West while Pacific moisture overtaking the Great Plains would prompt the development of snow from the Black Hills on south through the Central Plains.

Snow in the Central Plains and Midwest expanded thanks to two synoptic-scale features. The first was the emerging jet streak over Arizona and New Mexico as it placed its divergent left-exit region over eastern Colorado, central Nebraska, and western Iowa by the afternoon of February 14. Farther north and east, a second jet streak positioned over the northern Great Lakes placed its divergent right-entrance region over the Upper Mississippi Valley and the Michigan U.P.. As the upper trough over the Rockies moved eastward, strong ridging over Florida gave rise to a strong low-level anticyclone. When contrasting this ridging with the lower heights/pressure over the western U.S., this led to an accelerating low-level jet (LLJ) that directed rich Gulf moisture northward into the Midwest. This led to periods of snow through the night of February 14.

The most impactful day weather-wise came on February 15 as the upper trough in the West made its way into the Central U.S.. At jet stream level, winds continued to accelerate to the point where 200mb winds by 00Z February 16 surpassed 160 knots over the eastern Great Lakes. Its divergent right-entrance region aligned over the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley, while at the same time, a 50 knot 850mb jet supplied anomalous Gulf moisture over the region. To the north of a cold front traversing the Great Lakes, periods of heavy snow continued over the Michigan U.P. and the northern tip of Michigan’s Mitten. The tandem of troughing in the central U.S. and strong riding in the Southeast led to an expansive area of >300 kg/m/s IVT values by 00Z Feb 16 that stretched from the Gulf Coast to New England. In the northern Appalachians, snow would be the primary precipitation type. Farther south, from southern New England to the northern Mid-Atlantic, the stream of warm/moist southerly air caused a burgeoning warm-nose at low-levels, resulting in snow to changing over to sleet and freezing rain as far south as the central Appalachians the afternoon of February 15. This icy wintry mix led to accumulating ice with amounts over one-quarter inch for many locations. While a disruptive winter storm was the story in the northeastern U.S. and the Great Lakes, a deadly flash flooding event was unfolding from the Middle Mississippi River Valley to the Ohio Valley as WPC had issued a rare “High Risk” (level 4/4) for portions of this highlighted area. Highly anomalous moisture overrunning a stalled frontal boundary supported training segments of thunderstorms containing excessive rainfall rates over 1”/hr. These rainfall rates, combined with lingering snowpack and soil temperatures that were very cold, allowed rain to run off more efficiently and foster an even more supportive environment for flash flooding. Impacts as a result of this destructive flood event are listed in the Impacts section.

As the initial wave of warm-air advection-driven precipitation diminished the night of February 15, the warm front associated with the strengthening storm system in the Oho Valley marched north the morning of February 16. On the western flank of the 850mb low, located over Lake Erie at 12Z February 16, colder temperatures and increasing northerly winds would not only keep a band of synoptically-driven snow over eastern Michigan, but these winds would reinvigorate lake-effect snow bands over the Upper Great Lakes during the daytime hours on February 16, then over the eastern Great Lakes later that evening. By 00Z February 17, the storm had deepened to 979mb over Boston, MA, which was 20mb lower than the storm was 24 hours earlier over Memphis, TN. Periods of snow would continue over the northern Appalachians and much of Maine while numerous lake-effect snow streamers and upslope snow in the central Appalachians persisted. By 12Z February 17, the storm, now a powerful 964mb low, had raced over eastern Quebec with very cold temperatures and lake-effect snow bands lingering over the Michigan U.P. and in the snow belt areas of northern and western New York.

Impacts:

Focusing on the winter impacts first, as much as two to five feet of snowfall was measured in the Sierra Nevada, while one to two feet of snow blanketed mountain ranges from the tallest peaks of Southern California to the Central Rockies. Minor snow accumulations were also observed in lower-elevation areas such as the Portland, OR metro area. Schools in the Midwest were let out early on Friday, February 14 in advance of the snow’s arrival. A stripe of 6-10 inches of snow fell from eastern Nebraska and western Iowa to central Wisconsin between Friday evening and Saturday. The heaviest snowfall amounts came in the northern Great Lakes and the northern Appalachians where as much as one to two feet of snow accumulated there over the weekend of February 15-16. Some of this snow continued into Presidents’ Day in the snow belts of the Great Lakes with parts of Michigan’s U.P. and areas downwind of Lake Erie and Ontario seeing up to 2”/hour snowfall rates and whipping wind gusts. This caused significant reductions in visibility that made for whiteout conditions in these areas. Schools were closed for parts of the Upper Midwest on Friday, February 14, but the snow was a welcomed sight to ski resorts in the northern Appalachians. The storm’s heavy snowfall was linked as a potential reason for a building collapse in Massachusetts, and was also responsible for a plane crash in Toronto, Ontario.

Perhaps the most severe impacts from this winter storm came as a result of flash flooding and severe weather. In total, according to the Storm Prediction Center’s “Storm Reports” webpage, just under 300 filtered storm reports encompassed much of the Southeast from February 15-16.Of those reports, 25 of them were confirmed tornadoes, the majority of the tornadoes tracked across parts of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. The combination of tornadoes and damaging wind gusts left over 370,000 customers without power in Alabama and Georgia alone. The most deadly hazard was flash flooding that unfolded in Kentucky and Tennessee. Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear stated that swift-water rescue teams picked up and moved over 1,000 people. It was the combination of excessive rainfall rates and rapid snowmelt from the lingering snowpack that was still present in wake of a recent winter storm that led to tremendous run-off on mostly frozen ground. The Jackson, TN NWS Weather Forecast Office has their own Event Review on the storm, which mentions the following impacts: 10 fatalities, over 40,000 customers without power, 9,000 homes/businesses without water, and over 20,000 under boil water advisories.There were also 300+ roads closed, 14 reported mudslides, and one of those mudslides occurred on Interstate 69. First responders had to evacuate as many as 80 patients and staff from the Tug Valley Regional Hospital and 100 patients from the Landmark Nursing Home. In Tennessee’s Obion County, a levee near the town of Rives had failed and led to catastrophic flooding. Roughly 200 residents were in need of rescuing according to the Tipton County Fire Department.

Link to NWS WFO Jackson, KY's February 2025 Flooding Summary: https://www.weather.gov/lmk/KYFlooding